On October 13th, 2022, author Samira Ahmed posted a tweet on her Twitter with a screenshot of one of her direct messages that had been sent to her from a teenaged reader who’d been assigned her book for a class in school. This, to many of us who grew up in spaces and head spaces in which writers were just as unreachable as any other celebrity, is utterly bizarre. It’s bizarre in two fashions, the first being that someone believed this was an appropriate thing to send to a writer and the second being that the writer saw and reacted to it at all.

The accessibility of writers and other types of creators on things like Twitter and other social media is a little foreign for those of us who had to send our fan mail by post to a specific address purposefully publicized as meant for such things. Sometimes romance authors have an email address connected to their pen name just for those kinds of things. But how many of those emails or communications are threatening? And of them, how many get a response? Does every single one of them go to the police so they can determine if said communication is a credible threat? If they are determined not to be a credible threat, does the sender ever know that their emotional outburst caused any stir whatsoever?

Ahmed’s Twitter post riled up the frothing horde of the Twitterverse with some saying that it was absolutely horrid for her to have faced that kind of speech, encouraging her to reach out to the student’s school and see if there could be any talk that might impress upon kids that strangers require a modicum of formality. Others laughed at her response, replying that that’s “Just how they talk” in reference to Generation Z’s often irreverently violent speech and implying that if she were to intercede in any way that she may be the reason a child doesn’t read anymore. Others took it up a notch, trying to impress upon Ahmed that she was in fact the violent party by not blurring out the image of the student’s profile picture, potentially allowing them to be (theoretically) identified.

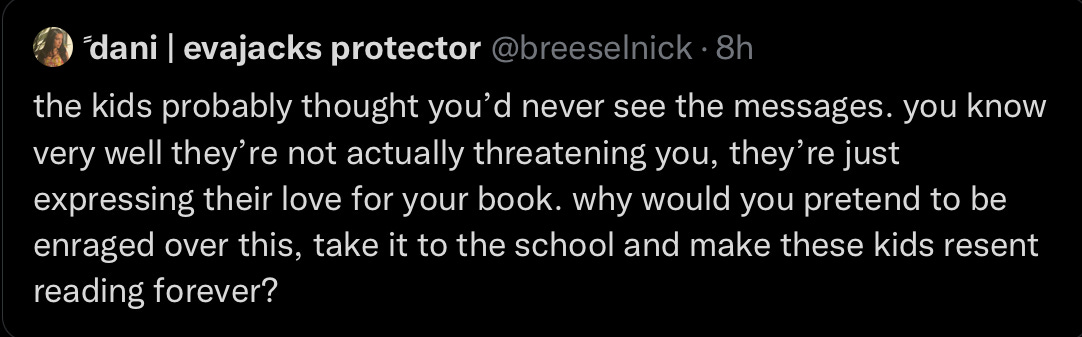

Twitter user @breeselnick tweeted “you know very well they’re not actually threatening you, they’re just expressing love for your book” and while it is common for strong positive emotions to cause some irrational anger-like (or depression-like) responses, is it truly fair of them to have also stated before this that the kids “probably thought [Ahmed would] never see the messages”? Would the kids be under the impression that someone else runs an author’s Twitter account? I suppose if it were Stephen King his mail could be screened but if a writer has their direct messages open, I would personally assume that those messages would be, well, direct. It may be unreasonable to assume that the kids in question are under the impression that their messages will not be read, as social media is nothing if not an efficient communication tool. As for the assumption that these are not credible threats: who’s to say? People have been murdered over smaller things and teenagers are notoriously hot-headed and maliciously stupid, how could one assume that their next speaking opportunity would not be met with at least one seething teenaged Annie Wilkes?

Is this a generational divide between the older generations and Gen-Z? Are the elder generations succumbing to the ever-constant of human nature in that they “just don’t understand” the new Generation’s expressions of emotion? Well, sure! But there’s something different about older generations’ perceptions about Gen-Z humor that must be resolved before this generational gap can be bridged—the ability to tell when an expression is a threat and Gen-Z’s ability to speak differently to strangers versus their friends.

The Manosphere, the Alt-Right, Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists, and other extremist movements that primarily find their largest audiences online have proliferated memes and “irony” into the rhetoric of youth. Teenagers, naturally, take it all to even further extremes, unable to mask their unironic hatred with terms and phrases that can have the benefit of the doubt enough to be considered ironic when it suits. They are introduced to the “ironic” hatred of women, LGBTQ+, and certain types of content creators but all of this, when repeated over and over, turns into an unironic belief—much of this belief hinging on the ever-growing paranoia that content creators are secret pedophiles. Laura Bates in her work Men Who Hate Women talks about the usage of these tactics within white supremacy and quotes Andrew Anglin of The Daily Stormer:

“The reader is at first drawn in by curiosity or the naughty humor, and is slowly awakened to reality by repeatedly reading the same points… The unindoctrinated should not be able to tell if we are joking or not.”

This tactic is based on the repetition of words and phrases and humor that resonates somewhere in the minds of those who are repeating it. On some level, the teenager who is “ironically” telling gay men to die really does believe in what they’re saying and the repetition and validation of those kinds of thoughts/jokes/humor through clout or engagement is what drives those ideologies forward and informs groups of kids whose social power is based on how much ironic hate they can exhibit. Naturally, some of the edgy teen shit does wear away when they age but much of it really doesn’t, they just get better at masking it.

Teenagers have a hard time with emotional regulation, social skills, and mental fortitude, it’s just a fact of life. But when we’re trying to determine if something is a problem or “just how they talk” we need to also consider the wider spectrum of influences both online and off. There are bad people who want children to make rage part of their personality. There are groups out there who revel in the ironic hatred of LGBTQ among Queer youth (self-hatred is a powerful tool for the alt-right) or ironic anti-Blackness among BIPOC. If kids are growing up next to the agitator of the rage machine, maybe how they talk is a pretty decent indicator of who they might grow up to be.